Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s original stories. Today we’re looking at “The Cats of Ulthar,” written in June 1920 and first published in the November 1920 issue of Tryout, and “The Other Gods,” written in August 1921 and first published in the November 1933 issue of The Fantasy Fan.

I don’t know about anyone else, but I’m finding the window that these dates/venues provide into fan-writing culture and rejection rates in the pulp era pretty interesting. Twelve years, yeesh!

Spoilers ahead.

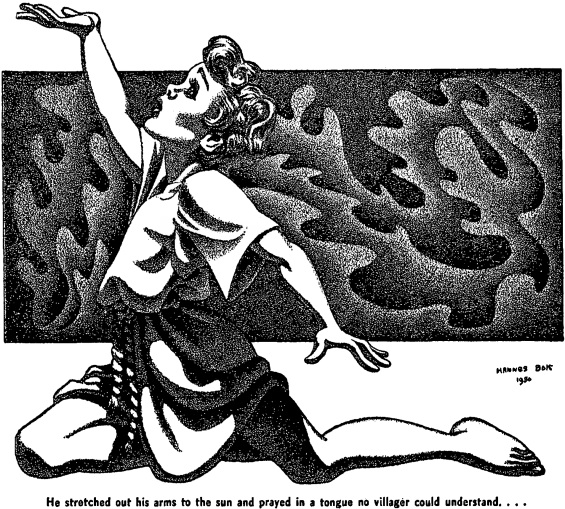

“He stretched out his arms toward the sun and prayed in a tongue no villager could understand; though indeed the villagers did not try very hard to understand, since their attention was mostly taken up by the sky and the odd shapes the clouds were assuming. It was very peculiar, but as the little boy uttered his petition there seemed to form overhead the shadowy, nebulous figures of exotic things; of hybrid creatures crowned with horn-flanked discs. Nature is full of such illusions to impress the imaginative.”

Cats of Ulthar—Summary

Inspired by the cat purring on his hearth, our magisterial narrator tells of the remarkable felines of Ulthar. Like all cats, they’re kin to jungle lords, older than the Sphinx, and see things humans cannot.

In the Dreamlands town of Ulthar lived an aged couple who nursed an inveterate hatred of cats and killed all they could. From the sounds issuing from their isolated cottage after dark, their methods were not merciful. The Ultharians lamented this slaughter, but were so mild-mannered they didn’t dare confront the assassins. Hey, the old creeps had scary expressions! And they lived in this tiny house under the oaks! Kind of like the Terrible Old Man of Kingsport! So the Ultharians kept their cats away from the weirdoes, and if their darlings got killed anyway, they thanked the gods it wasn’t their children.

Simple folk, the Ultharians—they didn’t know whence cats originally came.

Not so simple were the southern wanderers who drove into Ulthar one day. Their caravans bore paintings of men with the heads of hawks, rams, lions—and cats. They traded fortunes for silver, silver for beads. They prayed strangely. Among them was an orphan boy, Menes, whose only comfort was a black kitten.

The kitten disappeared. Townsfolk told Menes about the aged couple.

Now Menes wasn’t putting up with that crap. He stretched up his arms and prayed in an unknown tongue until the clouds reshaped themselves into hybrid creatures like those on the caravans.

Take that, kitten-killers! That is, wait for it, wait for it….

The wanderers wandered off that night. So, too, did every cat in Ulthar. Some blamed the wanderers, others the usual suspects. But Atal, the innkeeper’s son, claimed he’d seen all the cats in their enemies’ yard, solemnly pacing two abreast around the cottage.

The next morning every cat was back, fat and purring and not at all hungry. Eventually people noticed the couple’s lights unlit at night. They got up the nerve to check it out, and lo, they found two well-picked skeletons and curious beetles scuttling in the cottage’s dark corners.

After much discussion, the burgesses enacted a singular law. In Ulthar, no man may kill a cat.

The Other Gods—Summary

If there’s anything wussier than the townsfolk of Ulthar, it’s the gods of earth. They used to live on a bunch of mountaintops, but then men would scale the mountains, forcing the timid gods to flee to higher peaks. They end up on the highest peak of all, Kadath, in the cold waste which no man knows.

Occasionally they get homesick and sail to their old mountains on cloud-ships. They wreath the peaks with mist, and dance, and play, and weep softly. Men may feel their tears as rain or hear their sighs on the dawn wind, but they better not peek, because (like Menes) the gods aren’t taking that crap anymore.

In Ulthar lived an old priest named Barzai the Wise, who’d advised the burgesses on their law against killing cats. He’d read stuff like the Pnakotic Manuscripts, and was an expert on the gods to the point where he was deemed half-divine himself. Figuring this would shield him, he decided to climb Hatheg-Kla, a favorite resort of the gods, and gaze upon them as they danced.

He took along his disciple Atal (yes, that innkeeper’s son.) After trekking through the desert, they scaled Hatheg-Kla until the air grew icy and thin. Clouds sailed in to obscure the peak. Barzai knew these were the gods’ ships, and hurried upward, but Atal grew nervous and hung back.

From the high mists, he heard Barzai shout in delight: He hears the gods; they fear his coming because he’s greater than they! He’ll soon behold them as they dance in the moonlight!

But as Atal struggled to follow, an unpredicted eclipse extinguished the moon. Worse, the laws of earth bent, and he felt himself sucked up the steep slopes. Barzai’s triumph turned to terror—though he’d beheld the gods of earth, the OTHER GODS came to defend them, and they ruled the outer hells and infinite abysses, and oops, now Barzai was FALLING INTO THE SKY!

As monstrous thunder pealed, Atal leapt against the unearthly suction. Not having looked on the gods of earth, he was spared the sight of the OTHER GODS. When searchers climbed Hatheg-Kla, they found riven into the summit a symbol from the parts of the Pnakotic Manuscripts too ancient to be read.

Barzai was never found, however, and to this day the gods of earth love to dance on Hatheg-Kla, safe from men while the OTHER GODS protect their feeble selves.

What’s Cyclopean: When the townsfolk search Hatheg-Kla, they find a cyclopean symbol 50 cubits wide carved in the slope. A more impressive size than that listed in “Charles Dexter Ward.”

The Degenerate Dutch: Africa is “hoary and sinister.” Yes, the whole continent.

Mythos Making: The Pnakotic Manuscripts (previously described as a remnant of Atlantis’s fall, and containing hints of the Yith) link this story to the central Mythos.

Libronomicon: Barzai is familiar with the seven cryptical books of Hsan, as well as the Pnakotic Manuscripts. The latter describe Sansu’s earlier ascension of Hatheg-Kla, and include symbols like the cyclopean one later found on that same peak.

Madness Takes Its Toll: No one is officially mad here, though Barzai shows symptoms of Narcissistic Personality Disorder.

Anne’s Commentary

Cats of Ulthar

I paired these Dreamlands tales because they feature Ulthar and its favorite son Atal. They also share a theme with each other and “The Doom that Came to Sarnath”: Neighbors are hell. In fact, it can take divine intervention to deal with them.

Not only do Dreamlands folk have trouble getting along, they’re frequent speciesists. The harmless Ibites outraged the Sarnathians merely by walking in “the world of men.” The cats of Ulthar commit the same offense, daring to slink about of an evening and by their very felinity sparking the wrath of elderly ailurophobes. What is it with old people who live in houses under trees? That situation must be diagnostic of dark sorcery, because why else would the Ultharians be too afraid to confront the cat-killers? On the other hand, the Ultharians could be created in the image of the gods of earth, themselves timid beyond reason.

Apparently there are no Dreamlands branches of the SPCA or PETA. There are, however, wanderers from the Dreamlands annex of Egypt, by their trappings. They’re the opposite of the old couple, so far from speciesism that their gods are amalgams of man and beast. Nor do they put up with speciesist crap from others. Even a child among them has the balls to call in divine allies.

The Ultharians might ask, in their turn, whether it does take balls to confront evil when you can hand off the dirty work to gods. They may have a point, about which more later.

As with “Terrible Old Man” and “Doom,” we don’t get to see revenge enacted, just its aftermath. This gives us the amusement of imagining the carnage for ourselves. Do the wanderers’ gods kill the old couple, or do the cats? It’s clear the cats share in the subsequent feast, but what about those beetles? In keeping with the Egyptian motif, I thought of scarabs. I also thought of dermestid beetles, used to clean skeletons of every bit of flesh. They could have assisted the cats in picking the old couple’s bones. Or maybe—I like this one—the spirits of the couple were transmuted into bungling beetles, with which the cats may now sport at will.

In this story, the cats are initially passive, without agency against their persecutors. They have a latent ability to defend themselves, like their jungle cousins, but it seems to take the wanderers’ gods to potentiate them. If so, they stay potentiated. As we’ll see in Dream Quest, the cats of Ulthar take subsequent threats into their own collective paws and are some of Randolph Carter’s fiercest allies.

The Other Gods

“The Other Gods” could be viewed as a straight forward tale of hubris punished. I’m more interested in the gods of earth than in Barzai and his fate. The gods, after all, are the put-upon neighbors in this story. All they want is a little privacy, but these damn humans keep crashing their mountaintop tea dances! So gauche, so déclassé. So there goes the neighborhood. But is running away the solution? Deity up, gods! You ought to have called in conflict mediators long before the Other Gods had to get involved.

The Other Gods I equate with the Outer Gods who will finally become the stars of Lovecraft’s Mythos: Azathoth, Nyarlathotep, Yog-Sothoth, Shub-Niggurath. In Dream-Quest, Nyarlathotep, the Soul and Messenger, is clearly the liaison between the two sets of deities and the power behind the earth gods’ thrones. Here the Other Gods appear as a vast shadow that eclipses the moon and then vacuums up the overweening Barzai. Falling into the sky! What a wonderful reversal of earthly law, which reversal is always the hallmark of the Outer Gods and related entities, like the Cthulhu spawn with their non-Euclidean architecture.

As promised, a closing word about personal action. The Ultharians are beholden for justice to the wanderers, who are beholden to their beast-headed gods. The very gods of earth (including the wanderers’ gods?) are beholden to the Other/Outer Gods. Yikes, Dreamlands people both mortal and immortal are subject to the whims of the infinite abysses, the outermost chaos, the unfeeling forces of will that stir in the dark between planes! These early stories may have neat endings, but the philosophical way is paved for Lovecraft’s ultimate vision of man’s (in)significance in the cosmos.

The terror. The awe. The terrible and awesome coolness of it all.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

It’s been a long couple of weeks at Chez Emrys. As I write this (just after “The Unnamable” posted; we keep a bit of a cushion in our schedule), my 2-week-old daughter is nursing beside me and my 14-year-old cat is curled under the bed dying of cancer. All of which is not to invite socially normative expressions of congratulation and sympathy (though they’re much appreciated, I’d actually rather discuss Lovecraft), but to explain why 1) this commentary may end up a bit of a sleep-deprived ramble, and 2) I’m currently pretty generously inclined towards stories about why we ought to be nice to cats.

This in spite of the fact that when people go on about how dignified cats are, how they’re the heirs of Egypt and know all the secrets, I kind of want to roll my eyes. In my experience, cats really want to be dignified, but there they are eating cardboard like gerbils and lying splayed in ridiculous positions. Apparently this is a culture-wide shift in attitude. Even so, there’s something strange about cats: with dogs we humans have a longstanding symbiotic relationship to explain why we put up with each others follies, but cats are tiny predators that hang around our houses and exchange affection for affection and food. This isn’t the first time attitudes have shifted—I’m rather fond of the balance between holy sphinx and LOLcat in For I Will Consider My Cat Jeoffry.

Also reflecting a change in the culture, Ulthar’s “remarkable” law is now on the books in all 50 US states, and presumably many other places as well. We’ve gotten less worshipful of our feline companions, but more protective. Frankly, the Ultharites could have saved themselves a lot of trouble, and maybe gotten that nasty old couple to relocate in a hurry, by passing such a law earlier. Why is “jerks might get eaten” a good reason for the law, but “they keep sacrificing our pets” isn’t? Or is it the divine intervention that makes them think they ought to actually do something?

The Ultharites are “simple” for not knowing cats’ secret origin, and of course the story doesn’t tell us. One does get some hints. The nomadic fortune-tellers seem pretty trope-ish at first glance, but the animal-headed figures on their wagons suggest an Egyptian origin. Likewise the “singular” beetles—scarabs, perchance? Then we have the name of the young boy who actually calls in help—“Menes” sounds a little like the start of Mene, mene, tekel uparshin. Prophets threatening the fall of empires, again.

“The Other Gods” connects with “Cats,” somewhat tenuously, through Atal (presumably inspired to his apprenticeship by his experiences in the earlier story) and by Barzai the Wise’s retconned role in enacting the cat protection law. Possibly this backstory is meant to suggest that Barzai really was wise once—he certainly isn’t here. He may have read the Pnakotic Manuscripts, but he’s clearly never seen a single Greek tragedy, the Evil Overlord list, or any other warning against hubris and gloating. Once you announce your supremacy over the gods, it’s all over but the screaming.

The fuzziness between reality and metaphor seems appropriate to the Dreamlands. The gods really are up on those mountains, pushed back to taller and taller peaks by human exploration. But their presence is as much poetry as reality, as they withdraw from direct intervention. And some of those peaks, when everything in the ordinary world has been scaled, are in the Dreamlands. Reminds me of Gaiman’s Sandman, where dying gods withdraw to the Dreaming. Here, though, it’s not lack of belief that limits the gods, but humans trying to meet them on our own terms rather than theirs.

The changing gravity, as Barzai and Atal approach, makes me think of mystery spots, and are another blurring of the line between real-world physics and myth.

Speaking of myth, the most obvious question here is who the “other gods” are, and what they’re actually doing. This being Lovecraft, the obvious supposition is the extraterrestrial gods of the Mythos. But most of those can usually be found in specific places, and Hatheg-Kla ain’t one of them. Nyarlathotep, less settled than Cthulhu, might take some time out for god-guarding, a theory supported in later stories.

Also, what definition of “guard” are we using here? One guards prisoners, but one also guards things that can’t otherwise defend themselves. Are the terrifying other gods protecting the now-weak gods of earth from humans who want to push them further out—say, from Barzai? It certainly doesn’t sound like Earth’s gods are distressed by the whole thing, and after all “they know they are safe.” (Anne takes this interpretation in the summary—I agree, but think it’s meant to be a touch ambiguous. Otherwise why not abandon earth for Mons Olympus?)

Both these stories manage to keep linguistic excess in check, with some wonderful results. “Mists are the memories of gods,” made me pause for a moment of deep appreciation: a gorgeous, unadorned line with not an adjective to its name. It’s kind of a relief to know that we won’t be drowning in vinegar-soaked pearls every time we venture into the Dreamlands.

Next week, join us—along with the dreaming Abdul Alhazred—for a tour of “The Nameless City.”

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian novelette “The Litany of Earth” is available on Tor.com, along with the more recent but distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land.” Her work has also appeared at Strange Horizons and Analog. She can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal. She lives in a large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “Geldman’s Pharmacy” received honorable mention in The Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror, Thirteenth Annual Collection. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” is published on Tor.com, and her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen. She currently lives in a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island.